There are signs that in around 1849, Mescalero Apache watered their horses at the Mescalero Springs. Later, Mexican farmers dug canals by hand to irrigate their crops, which they later sold to people who lived in Fort Davis. The farmers called these springs the San Solomon Springs. In 1927, the springs were dredged and a canal was built to better utilize the flow of the water. Records show that the springs around Balmorhea have been in use for almost 11,000 years.

Photo by S. Resendez

In 1934, the State Board of Texas acquired approximately 46 acres around the San Solomon Springs. The Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) arrived at the springs in July 1934 and began work on building what would later become Balmorhea State Park. The CCC created the 1.3 acre pool around the springs. They also built the concession building, the bath houses, and the motel court using native limestone and hand hewn adobe bricks.

The San Solomon Springs is the largest in a series of 6 springs located in the Chihuahuan desert. The Balmorhea State Park Swimming Pool is the world’s largest spring-fed pool and often referred to as the crown jewel of the Texas State Parks System. The springs originally emptied into what is known as a ciénga or desert wetland. Construction of the swimming pool, back in 1934, resulted in the destruction of the natural springs which were rebuilt and fashioned into two man-made ciéngas.

There is an overlook by the RV section of the park for visitors to look for wildlife like deer, javelina, squirrels, turtles, lizards and dragonflies, which also utilize the springs. San Solomon Springs also serves as a stop for resident and migratory birds and is home to several rare and endangered species of snails and fish. San Solomon Springs is the largest spring in the Balmorhea area, and the habitat at Balmorhea State Park is very important for the conservation of these species.

Balmorhea State Park is located at 9207 TX-17, Toyahvale, TX 79786. Daily entrance fee for adults is $7 and free for children 12 and under. Park hours are from 8a to 7:30p or sunset (whichever comes first) and office hours are from 8a-5p. They often reach capacity and highly recommend reservations for both camping and day use. You can reserve passes online or by calling the customer service center before you visit. Check the park’s Facebook page for updates. Read their FAQ page for more detailed information about park and pool rules. Make sure you plan your visit before going!

Photo by S. Resendez

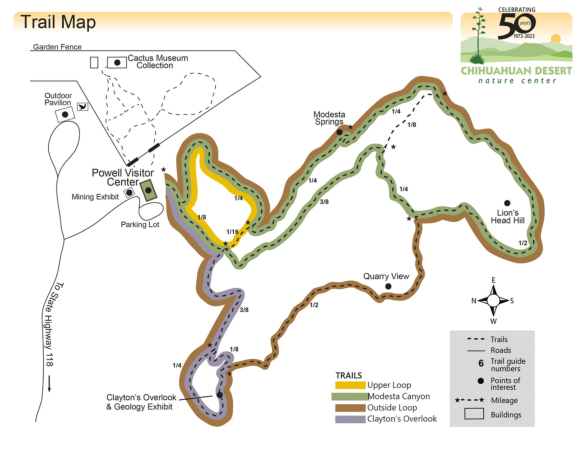

About 41 miles south and just outside of Fort Davis, Texas, sits the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center. The Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute (CDRI) is a nonprofit organization that was established in 1973 and housed in Alpine, Texas. Its principal founders were science professors at Sul Ross State University, a university that the institute continues to work closely with today. Today, the CDRI is the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center and is located on 507 acres in the foothills of the Davis Mountains.

The Nature Center is open year round. If you’re interested in exhibits about geology, history, and culture of the Chihuahuan desert, there is a mining exhibit detailing desert mining and the geological changes that have occurred in the Trans-Pecos of Texas over the last 2 billion years! A bird blind is available for birders, and there’s a cactus museum which houses over 200 species, sub-species, and varieties of cacti and succulents.

If you don’t feel like hiking, there are botanical gardens which encompass a wildscape garden, a self-guided stroll through a Trans Pecos Natives garden, a pollinator garden trail, and a native grasses exhibit.

Check the website for Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center before heading out. The Center is located off of Hwy 118, 4 miles SE of Fort Davis at 43869 St. Hwy. 118, Their hours are Monday-Saturday, 9a-5p.

MILE MARKER: Would you believe that cactus can be found as far north as Canada?! Some species have evolved to withstand cold temperatures and dry conditions. Southern prairies and certain regions by the Great Lakes, provide habitats with enough sun, well-drained soil, and suitable temperatures for cacti to thrive.

HIKE IT!: There are lots of great hiking trails at the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center. There are 5 trails ranging from .25 mile (scenic loop inside the botanical garden) to a 2.5 mile loop, which is considered a strenuous hike. Remember, you are hiking at an elevation of approximately 5,000 feet! Consider the weather and your own physical abilities. While the trails are mostly earthen, they may be uneven so take your hiking sticks, sunscreen, a good hat to cover your head and face, and plenty of water. After all, you’re desert hiking!