America was moving west and it wasn’t an easy trek. As settlers began making their way into and across the United States, there was a push to move westward in the 1800’s. Gold had been discovered, Spaniards were making inroads and discovering land and an abundance of natural resources. Places like Fort Davis were providing a safe respite from the wild west but it was taking time for get from one end of the country to the other. Wagon routes and months-long sea voyages were slowing progress. Many leaders—businessmen, politicians, and military planners—began calling for a faster, safer way to connect the nation, a nation dreaming of speed and connection.

But the idea stalled for years because Congress couldn’t agree on where the route should run. Northern states pushed for a northern path; Southern states demanded a southern one. The political deadlock broke only after the Civil War began, when Southern representatives (who preferred a southern route) withdrew from Congress. Suddenly, the northern-backed plan had a clear path forward.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act, officially launching the transcontinental railroad. The government supported it with land grants and loans, while two companies—the Union Pacific (building west from Omaha) and the Central Pacific (building east from Sacramento)—took on the construction. Their lines met in 1869 at Promontory Summit, Utah, forever transforming travel, trade, and the American West.

On May 10, 1869, officials from the Central Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad met at PromontorySummit, in Box Elder County, Utah, to drive the final, ceremonial spikes, linking the eastern and western United States by rail. In 1965, the site of the last spike on the transcontinental railroad was designated a National Historic Site. In March of 2019, the park’s designation was changed from a historic site to a historic park, just in time to for the commemoration on May 10, 2019, as America celebrated the 150th anniversary of the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad and recognizing the historic site as the Golden Spike National Historical Park.

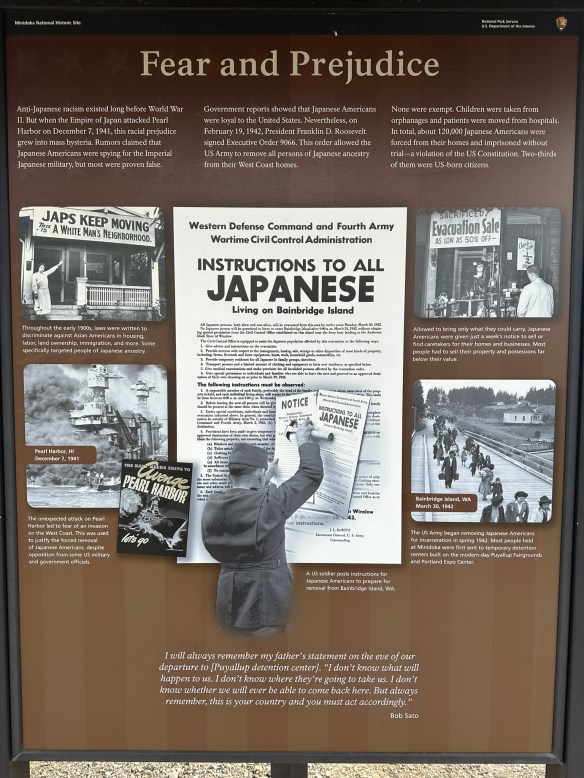

While connecting the railways was indeed a giant leap forward for the United States, it should be noted that these strides were made on the backs of several groups of people. Native Americans were already settled in the west and the construction of the railroad caused the people from 15 tribal nations to watch their homes and livelihood be destroyed with the advancement of the railroad. Irish immigrants, who came seeking work during potato famine in the mid-1800’s, were instrumental in helping build the railroad despite religious discrimination and.a language barrier. And Chinese immigrants, who were reluctantly hired after a critical shortage of labor was created due to gold strikes, were responsible for a great majority of the hardest labor that went into building the transcontinental railway. Chinese workers were often given tasked with working in the most dangerous conditions. Tunnels in the Sierra Nevada Mountains that had to be bored into solid granite for the railroad, rockslides, explosions, exposure, avalanches, and violent clashes claimed the lives of many of the Chinese workers. It is estimated that over one thousand Chinese laborers died building the CPRR. At the 1869 Golden Spike ceremony, not a single Chinese laborer was invited or mentioned, despite their indispensable role.

Photo courtesy NPS

Today, Golden Spike National Historical Park offers a variety of things to do during your visit. Commemorative events, seasonal events, nature, and hiking are all available at this park. There are approximately 55,000 visitors a year and the visitor’s center is open seasonally, at various hours. Please check the website for specific information before your visit. The physical address is 6200 North 22300 West, Promontory, Utah. It is approximately 30 miles west of Brigham City. The park is 2,735 acres of land surrounding a 15 mile stretch of the original Transcontinental Railroad. There is only one paved road coming in to the visitor’s center.

MILE MARKER: Did you know that the famous golden spike wasn’t hammered into place at all—it was gently tapped, lifted back out, and sent home, while the real work of joining the rails happened quietly behind the scenes.

HIKE IT!: There is a 1.5 mile trail called the Big Fill Loop Trail. It provides a beautiful view of the Promontory Mountains, the Great Salt Lake, and the Wasatch Front. Visitors can walk along the original grades of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads and still see drill marks from the tools used to create the tracks.