Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve is more than a stunning wilderness—it’s a living story of ice, culture, and resilience. Once completely covered by massive glaciers, this area is still reshaping itself, revealing dramatic fjords and thriving ecosystems. Home to Tlingit heritage sites, soaring mountains, and wildlife from bears to humpback whales, Glacier Bay invites you to explore its past while experiencing its raw, untamed beauty.

The time when the gradual shifting of glaciers began is now referred to as “The Little Ice Age”. It lasted for approximately 550 years and in addition to the extreme cold, there were periods of extreme climate fluctuation that made it difficult for any human beings to survive and thrive. Food scarcity and famine, disease and unrest, plagued the native populations and for at least the last 100 years into the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the Tlingit people were forced to gradually move off their ancestral lands.

But the shifting of the glaciers also brought out the mysteries of the land and suddenly, a new ecosystem was created which brought attention to the area in and around what we now call Glacier Bay. In 1925, when Glacier Bay became a National Monument, the land in and around Glacier Bay was the ancestral home to the four clans of the Huna (Hoonah) Łingít. In its attempt to preserve and conserve the natural beauty at Glacier Bay, the National Park Service (NPS) fostered new federal laws that severely impacted the lives of the indigenous people. Where they were once free to hunt, fish, and forage the land, new restrictions now curtailed, if not outright prohibited, the Huna Łingít’s ability to live freely on land that was once an integral part of their everyday lives.

In December of 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act that created Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. After becoming a national park, the National Park Service and Hoonah Indian Association, began working together to reestablish and reinvigorate traditional and cultural activities. There remains a concerted effort to collect and preserve oral history amongst the Hoonah. And on the shores of Bartlett Cove, a cooperative venture led to the first tribal house to honor the Glacier Bay since Łingít villages were destroyed by the moving glacier 250 years ago. The Huna Ancestor’s House is open to park visitors and provides opportunities to learn about Huna Łingít history, culture, and their ancestral way of life.

Accessibility: Bartlett Cove has a few short trails, a public dock, campground, Glacier Bay Lodge with the Park Visitor Center on the second level, and the Visitor Information Station. These paths are not paved, and may have exposed roots and rocks. The Tlingit Trail provides a wheelchair accessible gravel path between the public dock parking area and the front of the Huna Tribal House. While navigable by many new wheelchairs, not all trails meet ADA standards. There is also a beautiful wooden boardwalk that provides access to a viewing deck overlooking a serene pond. This 1/2-mile section of the Forest Trail is accessible and easy to negotiate. For more detailed information about accessibility, visit the Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve website.

MILE MARKER: When Captain George Vancouver sailed by in 1794, he didn’t discover Glacier Bay as we know it — because it was completely covered by ice. A single glacier more than 100 miles long and 4,000 feet thick filled the entire bay. By the late 1800s, the ice had already retreated over 30 miles, revealing the stunning fjords and waterways we see today.

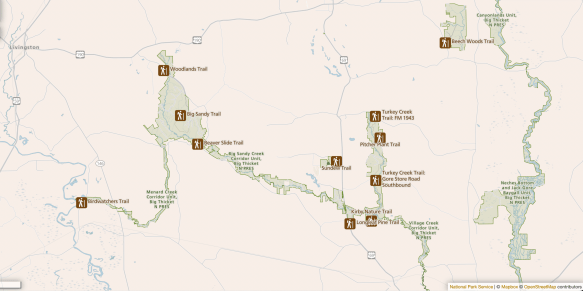

HIKE IT!:Several hiking trails are available to hike during your visit to Glacier Bay. You can view, or print, Bartlett Cove Trails Map for a simple visual of the shorter hiking trails. You can also visit the hiking page at the Glacier Bay NPS site. The best known hike at Glacier Bay would probably be the Forest Trail. It’s a 1 mile loop trail that’s rated as easy. The terrain is mostly flat and trail surface varies between dirt, gravel and boardwalk. There are benches and viewing platforms so factor in time to have a seat and enjoy nature. There is also a ranger led guided walk along this trail every afternoon.