Imagine a time when, if you wanted to travel down into Carlsbad Caverns, instead of hiking or taking an elevator down, you had to load yourself up into a big, old, guano harvesting bucket and have people lower you down. Would you do it? At one time, lots of people did! People wanted to know what sort of world was beneath the surface of the earth. What lives down there? What does it look like? What is it like to be below the surface of the earth?!

There was enough intrigue and curiosity about these caverns that in October of 1923, President Calvin Coolidge put out a proclamation denoting Carlsbad Caverns a National Monument. What is interesting about that proclamation is that even while recognizing Carlsbad as something that needed to be preserved, its size and depth were still not fully known. The proclamation itself uses phrases like, “extraordinary proportions” and “vast chambers of unknown character and dimensions” and even notes that there was, at that time, one entrance but also included “such other entrances as may be found”. Despite the unknown aspect, everyone recognized that it was in our nation’s best interest to protect this cave. In May of 1930, Carlsbad Caverns was fully established as a National Park.

Since then, we have learned that Carlsbad Caverns encompasses over 300 limestone caves in what was discovered to be a fossil reef that was “laid down by by an inland sea about 265 million years ago”. Above ground, there were signs that the land in that area had been utilized by Indigenous people, probably Mescalero Apaches, as early as 1200-1400 years ago. Spanish explorers showed up in the mid-1500’s and laid claim to the area. Eventually, as the Spaniards left, settlers worked their way through the Guadalupe Mountains. As time passed, travelers stopped in and around the general area and began to build ranches and farms. In 1898, a 16 year old farmhand by the name of Jim White entered the cave for the first time. Jim White eventually became the main guide to reporters, photographers, geologists, and geographers who wanted to learn more about the caverns. After passing away at the age of 63, for his exploration, guide services, and promotion of sharing the caverns with the public, he was unofficially honored with the title of “Mr. Carlsbad Caverns”.

In 1925, the first trail into the cave was built, eliminating the need to be lowered in a guano bucket. In 1963, the bat flight amphitheater was built at the natural entrance and began allowing visitors to sit and watch the bats take flight.

Today, if you’d like to visit Carlsbad Caverns National Park, you will need to go to their official NPS website and look for information on how to make a timed reservation or call 877-444-6777. In addition to making your timed reservation, expect to pay your entrance fee and to bring your ID along with your timed pass when it’s time for your visit. Cavern entrance hours are from 9:30a to 2:30p with the last reservation time being 2:15p.

If you’re only interested in watching the bat flight, you won’t need a reservation and there is no fee but seating at the amphitheater is first come, first serve, so get there early if you want to make sure you’ll have a place to sit. The bat flight program is held every evening from April through October. Bat flight takes place at the Bat Flight Amphitheater, which is located at the Natural Entrance to Carlsbad Cavern. The start time for the program changes as the summer progresses and sunset times change so make sure you check on the website before you head out. Bat flight programs may also be canceled due to inclimate weather, so again, check ahead of your visit! **Insider Tip** The best bat viewing months are August and September when baby bats born earlier in the summer begin flying with the colony. Also, migrating bats from colonies further north often join in the flights. Are you a morning person? Early risers (approx. 4-6 a.m.) can watch for the bats as they re-enter the cavern! Bat entrances often come with spectacular dives from heights of hundreds of feet. Remember: To protect the bats, electronic devices are not allowed at the Bat Flight Program and surrounding area. Electronic devices include cameras of any kind, laptop computers, cell phones, iPads, iPods, tablets, and MP3 players.

If you’ve never been to Carlsbad Caverns, the NPS website offers a webpage designed for first time visitors. Make sure you visit it for more detailed information about what to expect for your visit to the cave. Visitor hours are from 9a to 5p. Cave hours are from 9:30a to 2:30p. The last elevator coming OUT of the cavern is at 4:45p. If you decide you’d prefer to hike out, you must begin by 2:30 pm and plan to complete your hike out by 3:30 pm.

Accessibility: The Natural Entrance Trail is not Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant due to its steep grade (15%–20%) and therefore not accessible with wheelchairs; however, the Big Room Trail is accessible by elevator once you enter the underground rest area. This is a “one mile trail that is wet from dripping water and can be slippery, bumpy, uneven, and difficult to navigate. It is not Americans with Disabilities Act approved and should only be attempted with assistance. Maps defining the wheelchair accessible areas can be obtained in the visitor center. Due to steep grades and narrowness of the trail, barriers, and signs have been installed to note the portions that are inaccessible in a wheelchair.” There is an accessibility guide brochure available at the Visitor Center with more detailed information.

MILE MARKER: Did you know that Carlsbad Caverns was part of an ancient fossilized reef in a long-gone inland sea?! Instead of fish, coral, and sea sponges, you now have towering stalagmites, stalactites, and weird cave formations made from limestone that was once alive with marine life. You’re literally walking through the skeleton of a prehistoric ocean!!

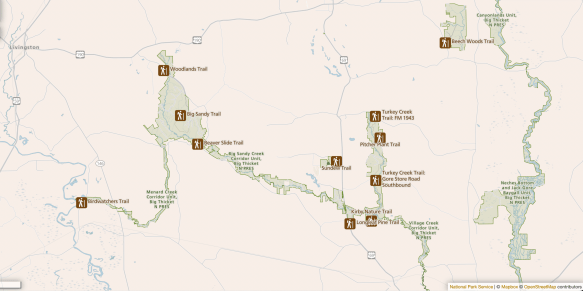

HIKE IT!: If you decide to venture into the caverns and choose to walk down using the Big Room route instead of taking the elevator, you will have hike approximately 1.25 miles. The walk is relatively flat and will take you approximately 1.5 hours to (average) to walk. There is a shorter route available which is about .6 mile and will take approximately 45 minutes (average) to complete. Only clear water is allowed in the cavern. Also, hiking sticks are not allowed unless medically necessary. If you’re interested in a surface hike, there are trails in and around the area. Check here for back country trail information prior to making your plans as some of these trails have been subject to repair and renovation after a flood in 2022.