Minidoka, one of ten incarceration sites established during World War II, stands as a powerful reminder of the injustices faced by Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes during the onset of World War II.

In the 1880’s, Japanese immigrants began making their way to America, primarily to Hawai’i, where they worked in the sugar plantations. From there, many Japanese immigrants made their way to the mainland where they worked clearing mines, building the railroad, at sawmills, and in the fields. This was due in part to The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was the first significant law prohibiting immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years.

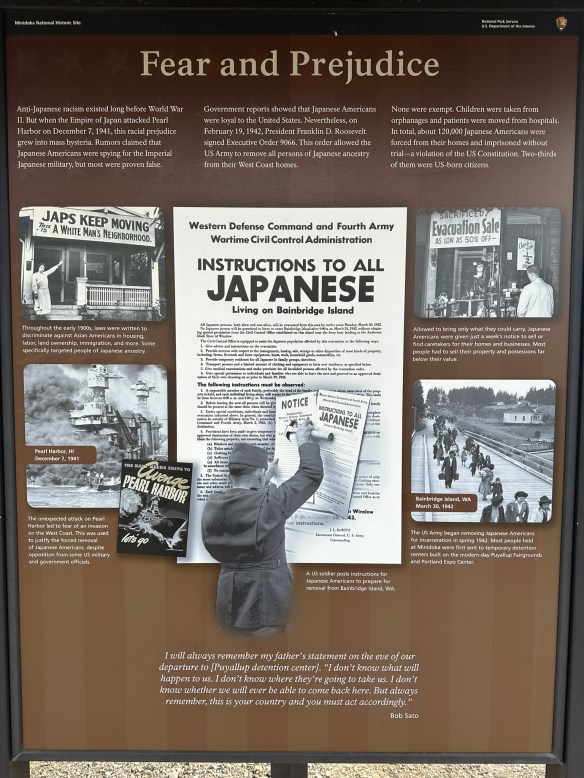

By the early 1900’s, Japanese families had assimilated into American culture. With a strong presence in Hawai’i and along the entire west coast of the United States, Japanese American families were fully productive members of society. They were business owners, educators, entrepreneurs, and neighbors. Despite lingering racist sentiment, much of it stemming from the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, Japanese-American families had tentatively created a place for themselves in America. Then, on December 7, 1941, Imperial Japan launched an unprovoked attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States declared war with Japan and life for Japanese Americans immediately changed.

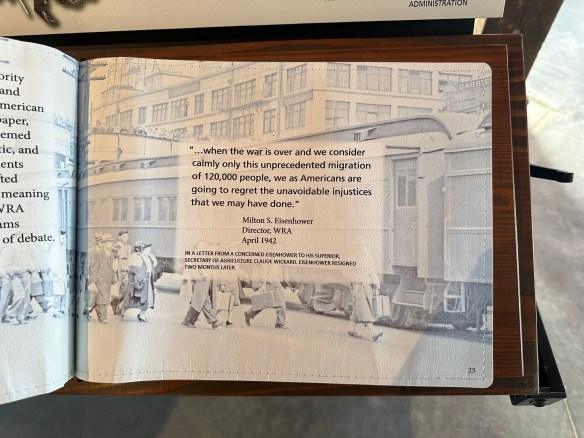

Predicated by the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, declaring certain areas within the United States as “war zones” thus enacting the removal of any and all Japanese Americans from their homes, forcing them into imprisonment without the benefit of due process. This remained in effect for the duration of the war. Despite some opposition and varied court cases filed against it, the executive order was not overturned until 1944.

Japanese Americans were first sent to temporary detention facilities, usually animal stables, racetracks, or fair grounds, and were held there until they were transported to their assigned War Relocation Camp. Ten major camps were set up for Japanese-American relocations. Minidoka was just one of them.

Minidoka National Historic Site is located in Jerome, Idaho, in the south-central part, not too far from Twin Falls. The concentration camp sat on approximately 33,000 acres and housed approximately 13,000 people, mostly from Washington, Oregon, and Alaska. The compound consisted of over 600 buildings, including the barracks where families lived. Before families arrived at Minidoka, they were given little to no notice that they had to vacate their homes. They were not allowed to bring anything they could not carry themselves.

Upon arrival at Minidoka, the prisoners learned that the camp was barely able to house all the incoming. Barracks had been hastily built using green wood and tar paper. One young man wrote of getting off the bus and walking into a dust storm. The minimally built shelters did nothing to keep out the elements as the green wood shrank and created gaps for the wind, dust, and rain to get through. There was no privacy in the large, shared buildings, and as an added insult to injury, prisoners were forced into labor, building more of the barracks that would be needed to house the hundreds of people coming in daily. Even the plumbing and sewage system wouldn’t be completed for several months. Across the nation, over 120,000 people were forced to live in these camps, in horrific conditions, with many of them being U.S. citizens,

Minidoka consisted of 36 residential blocks with 12 barracks, a mess hall, and a latrine. Each barrack was 120’x 20’, which was divided into six units. Each unit housed a family or a group of individuals. Each unit had one lightbulb and one coal burning stove. The walls dividing the units did not extend to the ceiling and the barracks had no insulation. Bathrooms consisted of a row of toilets and a row of showers. There were no partitions or dividing walls. Each block held a mess hall which served as a “hub” of sorts for families to gather and eat and hold community events like holiday parties or dances.

While not ideal, the families and individuals living within the concentration camp made the best they could of their situation. They educated their children in makeshift schools. They created sports teams, building a baseball field and basketball courts so they could play. They hosted cultural events amongst themselves, held religious services, and even published their own newspaper. The Japanese American people proved to be resourceful as well as resilient.

While in the concentration camps, males were offered the “opportunity” to serve their country as long as they signed acknowledgment and swore “unqualified allegiance” to the US and that they also forswore allegiance to any foreign power, including the Japanese Emperor. Most of the interred men wanted to serve their country but were angry at having to declare their allegiance to a country for which they never gave up their allegiance. How could they renounce allegiance to an emperor they never swore allegiance to in the first place? In the end, the men who decided to answer “no” to the questions regarding their allegiance were removed from the internment camps and sent to high security camps or detention centers. Most of the 30,000 Japanese American men who saw battle became part of 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion, with many still who became part of the Company B of the 1800th Engineering Battalion. In all, they were awarded six Distinguished Service Crosses during the first eight weeks of combat and three Presidential Unit Citations. Eventually, joining the 442nd Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion, Company B of the 1800th Engineering Battalion is often recognized as the most decorated American unit for its size and length of service.

In late 1944, in the case of Ex parte Mitsuye Endo, the Supreme Court ruled that Executive Order 9066 was unconstitutional. Also being reviewed by the Supreme Court in 1944, was the case Korematsu v. United States. In this case, (which was happening at almost the exact, same time as the Mitsuye Endo case) the use of the internment camps was upheld and is often cited as “one of the worst Supreme Court cases of all times”. In his dissent, Justice Frank Murphy said this,

I dissent, therefore, from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life. It is unattractive in any setting, but it is utterly revolting among a free people who have embraced the principles set forth in the Constitution of the United States. All residents of this nation are kin in some way by blood or culture to a foreign land. Yet they are primarily and necessarily a part of the new and distinct civilization of the United States. They must, accordingly, be treated at all times as the heirs of the American experiment, and as entitled to all the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution.~~Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (Supreme Court of the United States 1944)

When the camps closed and the prisoners were released, they were given the paltry sum of $25 and a one-way bus or train ticket to the destination of their choice. Despite the fact that the war was over and the despite the fact that Japanese Americans fought for their country alongside other American soldiers, anti-Japanese sentiments made integrating back into their communities difficult.

After the war ended, President Truman signed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948. This entitled anyone who was incarcerated to file claims for damages and loss of property but reparations did not come close to the $148 million dollars claimed. Only $37 million dollars had been allocated for damages. After the Civil Rights Movement, reparations were again sought and in 1980, the commission on Wartime Relocation and Incarceration of Civilians was signed into law. They discovered that the incarceration was the result of “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” In 1988, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was formalized, with President Ronald Reagan formally acknowledging the unconstitutional nature of the internment camps. Japanese Americans who were wrongfully imprisoned finally received reparations of $20,000 along with a formal apology.

Survivors and family members, friends, and allies of the people who were incarcerated at Minidoka participate in an annual pilgrimage. To learn more about their pilgrimage, click here.

The Minidoka Visitor Center is located at 1428 Hunt Road in Jerome, Idaho. If the visitor center is not open during your visit, you can check the after hours box for brochures. The historic site grounds are open year-round for self-guided walking tours. The Visitor Center is open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday from 10a to 5p. Restrooms are unavailable if the Visitor Center is closed.

The books mentioned in the podcast are Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II by Daniel James Brown and The Train to Crystal City: FDR’s Secret Prisoner Exchange Program and America’s Only Family Internment Camp During World War II by Jan Jarboe Russell

MILE MARKER: Despite the limited rations given at the internment camp, residents created gardens, grew crops, built hog and poultry farms and became completely self-sustainable. They even managed to create their own tofu plants.

HIKE IT!: Minidoka National Historic Site offers 1.6 miles (2.5 km) of gravel walking trails which is basically a self-guided tour of the grounds. It is essentially flat and not difficult to navigate on foot. It is not considered an “accessible” trail. There is plenty to see and read along the route. The sign boards offer stories of information regarding the activities on the land.