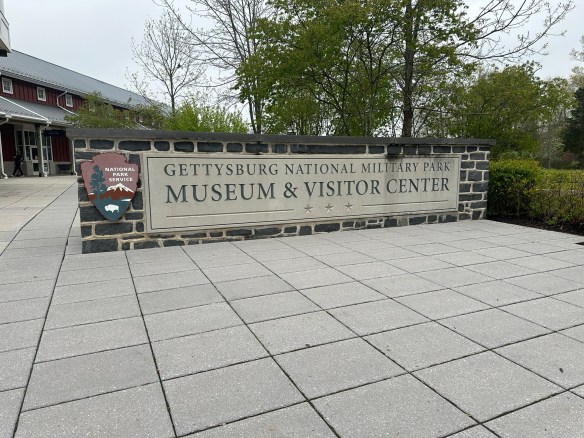

Gettysburg is where the nation turned and where a battlefield became sacred ground. Gettysburg National Military Park preserves the site of the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil and a turning point in the Civil War. More than 51,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or declared missing in just three days. The battle ensued across rolling farmland, rocky hills, orchards, and small town streets. The battle erupted almost accidentally when Confederate troops encountered Union cavalry near the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. What began as a scouting expedition quickly escalated into a massive three-day engagement involving over 165,000 soldiers.

After the battle, local citizens worked to recover bodies and care for the wounded. A Soldiers’ National Cemetery was created for Union dead. It was here that President Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address in November 1863 — redefining the war as a struggle not just for union, but for equality and democracy.

The Battle of Gettysburg is important for several reasons:

- It Stopped the Confederate Invasion of the North–General Robert E. Lee hoped to win a major victory on Northern soil, potentially forcing peace negotiations. Instead, his army suffered devastating losses and had to retreat back to Virginia.

- It Shifted Momentum Toward the Union–After Gettysburg, the Confederacy never again launched a full-scale invasion of the North. The Union gained confidence and strategic advantage.

- It Redefined the Meaning of the War–Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address framed the war as a fight for equality and democratic ideals — not simply preservation of the Union.

- It Became a Symbol of Sacrifice and Unity–Gettysburg represents the cost of division and the power of reconciliation — something visitors still feel walking the fields today.

Photo courtesy of NPS

Today, the park protects over 6,000 acres, with more than 1,300 monuments, markers, and memorials, making it one of the most monument-dense historic landscapes in the world. Visitors can hike the same ridgelines and walk the same fields where Union and Confederate soldiers fought, often within feet of original stone walls, farm buildings, and cannon placements. It serves as a perfect junction for hikers and history lovers alike, it’s a rare place where the outdoors and American identity intersect.

Park hours for Gettysburg National Military Park are from sunrise to sunset. The battlefield and roads are open thirty minutes before sunrise to thirty minutes after sunset. Visitors can plan their visit and obtain a listing of sunrise and sunset times by day in Gettysburg, PA here. Visitor Center hours change by season so make sure you check the website for more detailed information.

MILE MARKER: Did you know Gettysburg almost became an amusement park?

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, parts of the battlefield were treated more like a tourist playground than sacred ground. There were trolley lines, picnic groves, dance pavilions, and even proposals for roller coasters and a Ferris wheel near key battle sites. Visitors could ride out to the battlefield for leisure outings, not reflection. It wasn’t until preservation groups and the federal government stepped in that large sections of the land were protected and restored to their historic appearance.

HIKE IT!: There are no hiking trails in the park but that doesn’t mean you won’t be getting your steps in. Places in the park like Gettysburg National Cemetery or taking a Gettysburg Battle Walk will make sure you get your exercise. Just check the weather and plan accordingly.